Central Council Education Committee

Learning Together - 5

Learning Together - 5

“Dodging” appears over horizon

by Peter Dale

These articles are intended to offer self-help to bands consisting mainly of learners, whose tower captain also has little if any knowledge of elementary change ringing. Let us suppose that you, the reader, are in the position of that tower leader. Ultimately it’s up to you to maintain Sunday ringing, so it’s your responsibility to encourage your band to attend regularly. They need to feel that they are making progress, otherwise attendance may fall off and it will be difficult to retain recruits.

This series began gently by encouraging you to look out for handling faults and to aim for well-struck rounds. It continued by describing how to make a pair of bells swap places without upsetting the rhythm and showed you how, with a little imagination, you could develop this basic technique in various ways. You can thus retain your ringers’ interest by progressing gradually on to more involved combinations, but at the same time keeping within their limitations. Last time it was the Mexican Wave.

There was also a rather too brief a look at Whitefield Places. A more experienced band may not find a use for Whitefield, but it could be very helpful to prepare your ringers for their first attempt at “proper” method ringing. A very simple step forward from Whitefield is Plain Hunt Minimus. “Minimus” is a term used to describe methods where four bells only are involved in the changes.

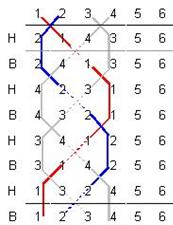

You may recall the diagram for Whitefield Places, see fig i,. Compare it with fig ii, the diagram for Plain Hunt:

fig i - Whitefield fig ii - Plain Hunt

A fairly obvious variation on Whitefield suggested in the last article would be for 1 and 4 to make the places, with 2 and 3 crossing in the middle. If your band becomes thoroughly familiar with both these versions of Whitefield then Plain Hunt won’t be totally new work, and it will have a very good chance of success at the first attempt.

In Whitefield, only two bells cross over in the middle, while the other two keep plodding away making places. In Plain Hunt Minimus all the bells in turn work their way across the middle and make a place at the “front” and “at the back”, as fig ii shows.

Be aware that some members of your band might prefer to turn the diagram “sideways”, as in fig iii, because they find it easier to visualise going “up” to 4th’s place and coming “down” to the lead. In fact there are many ringers who turn their method book sideways to look at methods like this.

fig iii

Using only four bells is sensible at this stage because a band of novices can understand and see what’s going on, much more easily than they can on five or more bells. The two “cover” bells, 5 and 6, are a steadying influence and also give the rounds-only ringers more opportunities to ring. It’s a good idea to brief your band about the order of the bells with whom they will swap. Knowing the “coursing order” is a crutch for your learners to lean on while they master the movements involved in “hunting”.

If you and your ringers have been working together successfully through all the suggestions in this series, from simple swapping pairs through to Plain Hunt Minimus, then you can justly feel a sense of achievement. Your ringing will impress the congregation, and you will have established a path of progression to support the next generation of beginners. You may now rest a little on your laurels to consolidate what you have learnt, but don’t become complacent because there’s a new challenge coming over the horizon.

Plain Hunt on four bells has only eight rows, and no two are the same. You can easily check that for yourself. However, mathematics tells us that in total there are twenty-four different rows possible on four bells. So there are sixteen more rows that don’t occur in Plain Hunt. This rather begs the question of how to access these sixteen other rows, and the answer is to introduce a manoeuvre known as a “dodge”.

The next article will explain what exactly is a “dodge”, and will examine it in some detail. Before you and your ringers can be expected to execute a dodge successfully you will first need to practise the technique, all together, within the context of rounds. Once your band has mastered dodging they will have much more success when they progress from Plain Hunt on to their first method.

In the mean time, some preparatory practice won’t go amiss.

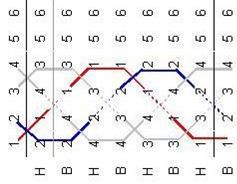

You may recall the three fundamental exercises described in the third article; fig iv is a reminder of these.

fig iv

Dodging is the most difficult of the three, so it was rather swept under the carpet for the time being because you already had quite enough to do at that stage. Now that your ringers have mastered the places exercises, and can ring several different variations of them, it’s high time they tried continuous dodging, if they haven’t already done so. Like the popular Latin American dance, it takes two to dodge.

Ringers A and B are the dodging partners in this illustration and one of them has to work rather harder than the other. Let’s think about why that is, and see who has the easier task.

In a typical tower, if there is such a place, about forty or more feet of rope rises and falls at each whole pull. That length of rope together with the sally has some appreciable weight, three or four pounds or two kilogrammes say, and this is highly significant. After the sally is released at a handstroke the bell lifts the rope, which in effect becomes a deadweight exerting a drag on the bell. Unless the ringer puts in the effort to overcome this, the bell will tend to drop short of the balance at the backstroke.

On the other hand, the weight of the falling rope at a backstroke acts in the ringer’s favour and helps to turn the bell round, giving the sally a natural tendency to rise at the handstroke. This can have a noticeable influence upon the behaviour of the bell, particularly in the dodging where it clearly favours A, who must pause at each handstroke and ring earlier at each backstroke.

B has drawn the shorter straw and must do some work to counteract the effect of the rope’s weight, preventing the sally from rising at the handstroke whilst putting in enough effort to make the backstrokes rise. This is a very fine point but if your learners can grasp the principle, then their dodging technique will be much more elegant and effective.

There are many methods in which the treble is never required to dodge but always “hunts” up and down. More experienced bands often place a learner on the treble for extra hunting practice, while they ring something more complicated. You can’t do this of course because everyone in your tower is a learner. Ideally you need a method that has dodges, which all of you can learn together. These methods do exist and the next article in the series will introduce at least one of them.