The Learning Curve - A regular feature in The Ringing World, by John Harrison.

Sponsored by the Central Council Education Committee

www.cccbr.org.uk/education/

Fighting the bell

(Volume 1, Chapter 29)

Ringing tutors see two problems over and over. They happen to most learners at some stage, but some ringers well past 'learners' suffer too. The two battles are fought in opposite directions: one to stop the bell dropping and the other to stop it crashing onto the stay. Needless to say, both drain a lot of energy from the hapless victim and both ruin the striking.

Getting wound up

We are told not to over-pull (at least we should be) but heeding the advice is not always so easy. No one consciously thinks 'I will ignore that advice' but lots of ringers, especially inexperienced ones, end up over pulling none the less. Some times as well as wasting effort and striking poorly, they risk failing to stop the bell crashing through the stay. So why does it happen, and what can you do about it?

Getting wound up is a good description of how

it feels - quite frightening if you don't know what

is happening. At first things might be OK and

then you find they get worse and worse, as if the

bell is fighting you. In one sense it is, but

remember that any excess energy in the bell came

from you. You can't blame a 'fast ball' on an

opponent - there is no one else on the rope. If the

bell sends you a 'fast one', it was you who pulled

it too hard on the previous stroke.

Of course you knew that the previous stroke

was a hard pull, but didn't realise that as well as

struggling with what came at you, you were

helping to make the next stroke worse as well.

Pulling and Checking

Let's go back to basics. Making the bell do

what you want is not just about 'pulling'; it is very

much about timing, ie when to apply force to the

rope. This is so important that many ringers use two different words:

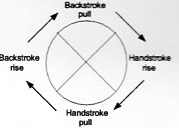

• Pulling means applying force as the rope descends; it makes the bell swing higher and therefore more slowly.

• Checking means applying force as the rope

rises; it stops the bell swinging so high, so it then

swings more quickly.

You can think of this as a four-stroke cycle,

shown diagrammatically in figure 1.

Figure 1 - The Four-stroke cycle

To be in control you need a balance between

pulling and checking, ie between force on the

rising and descending strokes. This might seem

obvious, but it is not easy until you get the hang of

it. The rise and fall of the rope at each stroke

follow in quick succession. Your arms should

make a smooth, continuous movement, but that

can hide the need for different force at different

parts of the stroke.

Switching the force

You must be able to 'switch on' or 'switch off' the force between the rise and fall, in order to vary the balance between pulling and checking. If you don't switch at the top of the stroke, you apply the same force on the way down as on the way up, which does little but wear you out. Worse still, most of us find pulling more natural than checking, so when really struggling, it's easy to pull a little more than you are checking.

Risk factors

Getting tired can increase the risk. You might

think it would reduce over-pulling, but when tired

you respond a little more slowly, and delay biases

you towards pulling. Of course, if you don't

understand the difference between pulling and

checking, it won't help either.

Unwinding

To unwind, you need to apply less force, but

you can't just stop suddenly, or the bell would

rush up and hit the stay with possibly disastrous

consequences. To get back to normal, you must

pull less while still checking quite hard (to handle

the excess energy already in the bell). Resist the

urge to follow through after the check with a

correspondingly vigorous pull.

Getting out of the wind-up is harder than

avoiding it in the first place. You might need to

do it over a few successive strokes, rather than in

one go. Be prepared also to handle any side

effects of drastic action, such as over-correcting,

or getting slightly out of place.

Dropping

The other common battle ringers fight is when

a bell continually seems to drop, despite

considerable efforts to keep it up. One expects a

badly going bell to cause problems, but when it

happens with a normal bell, it is often to do with

how it is being rung - you put a lot of effort in but

somehow it all gets dissipated.

This problem too is about pulling and checking.

The pulling is there for all to see, and the poor

soul on the end of the rope cannot intend to check

the bell, so how does it happen? Heavy

handedness is often the culprit.

Feeling v pulling

The rope is the only contact between you and

the bell. To feel what the bell is doing you must

keep the rope taut for as long as possible, but if

you keep it too tight, two things happen:

• The force affects the bell movement, even

when you don't intend it to.

• Your muscles are tighter, your feel for the

bell is less sensitive.

It can be very tempting to start pulling before the top of the swing, but if you do that, you don't feel how far the bell could have risen (especially at backstroke). In any case, it will not rise far because you are checking it. Cutting the rise short in this way is quite common, and defeats your efforts to keep the bell up.

The effect is most marked with a bell that is not

swinging up to the balance, ie when ringing

round the back, or when ringing up. There is no

clear point at which the bell goes over the balance

- near the top of the stroke it moves more slowly,

and is very sensitive to the force on the rope. It is

easy to misjudge this.

If you ring a heavier bell than normal, you need

to adapt to the way heavy bells swing. With a

bigger wheel, the rope goes up further, so if you

catch it as you would a smaller bell, you will find

your hands too high on the sally, thus checking it

involuntarily. The secret at handstroke, when

your hands rise to meet the sally, is to mirror the

rhythm of your hands at backstroke, which also

has a longer stroke.

With a small bell, even the weight of your arms

on the rope can cause problems, especially during

the up stroke, so you must support some (but not

all) of their weight. To do that without letting the

rope go slack requires an acute feel for what the

bell is doing, so you can move your hands at

exactly the same speed as the rope.

A long pull

Another thing everyone is (or should be) told, is

to maintain sustained downward tension on the

rope for as long as practical. This ensures a well

behaved rope (with less chance to swing

sideways). It also makes whatever force you

apply more effective, so a long gentle pull can

achieve more than a short jerk. If your arms stop

part way down, you are wasting some of the

stroke and making things harder.

Striking the balance

Precision control of anything from a bell to a

bicycle, involves finding and keeping a balance

between opposite trends. With a bike, falling off

to right or left feels the same (except where you

get bruised) and the correction mechanisms are

obvious, though over correction can cause

wobbling.

With ringing too, over correction is a problem,

if you don't anticipate when you have nearly

corrected things and back off. What makes

ringing harder is that a bell feels very different

when dropping or going too high. Add to that the

counter intuitive fact that pulling the bell makes it

ring more slowly rather than more quickly, and

the rather unhelpful fact that when you need to

pull most (because your bell is dropping) your

rope goes floppy, and it is not hard to see why so

many ringers struggle.

Solving the problem

You can avoid the problems if you:

a - understand what happens

b - can feel what your bell is doing

c - can 'switch' the force during the stroke

These are inter-dependent. You need (b) to

know when to do (c) and you need (a) to make

sense of it all. The key is the feeling - something

you need to keep on developing after mastering

the basic ability to handle the bell. Exercises like

ringing to the balance with extended pauses (not

touching the stay) are not just for beginners.

Doing it ten times on the run at hand and back is a

useful competence test that all of us should

occasionally try to perfect.

Another useful exercise is to reduce the overall

force on the rope (without letting the rope go

slack) while maintaining full control of your bell.

A light touch makes it easier to feel what is

happening, and easier to switch the force on and

off exactly as needed.

If you have problems with these exercises, try

adjusting your rope length. Half an inch can turn

good control into only adequate control. Two or

three inches can make it impossible. Practice

making continual adjustments and learn what the

right length feels like. Learn to adjust the length

while ringing.

Reprinted from The Ringing World 2 November 2001. To subscribe, see www.ringingworld.co.uk/ or call 01264 366620

Collections of monthly Learning Curve articles are available in book form from CC Publications www.cccbr.org.uk/pubs/

or they are free to read at www.cccbr.org.uk/education/thelearningcurve/