Walter George Ralph’s Story

(known as George)

Bell Ringer – St Mary’s Church

Baptised Stoke sub Hamdon 30 March 1890

Died Saturday 16th September 1916.

Researched and written by Angela Hodges of Stoke Sub Hamdon

We know very little about George Ralph himself except that he was thin and, if all the initials GR scratched on the walls of the ringing chamber were done by him, he had a mania for writing his name on walls.

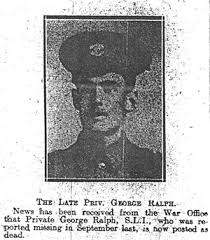

His photograph, posted in the Western Gazette when news eventually came through of his death the previous September, shows a slender, serious young man with heavy eyebrows and deep set eyes.

George was a native of Stoke under Ham, baptised in this church in 1890. His grandparents, Job and Elizabeth Ralph, however, were both born in Martock, as was his father, John.

By 1871, John had moved in Preston Plucknett in Yeovil, and was working as a packer. They were a family of four: John’s Devon born wife, Eliza, aged 20, daughter Susan aged three, and the baby, William Ernest.

Two years later Eliza died, aged 31, and in the summer of 1877, John married again – Emma Smith of Sydling St Nicholas – George’s mother. There were to be four children of this second marriage: Daniel, Elizabeth Annie, Frederick Arthur and Walter George. Of John’s six children, two would die in childhood and the youngest would be killed in the War as a young man in his twenties.

We know that by 1878, the family had moved to Stoke sub Hamdon, because there is a sad entry in the Stoke School Log Book for 5th July 1878:

Susan Ralph after leaving school on Monday afternoon about half past four, appears to have climbed up to the top of a wagon body that rested against a wall. Bessie Lock was at one end and Eva Weakley inside. The wagon fell and crushed Susan Ralph to death.

A year later, John and Emma’s first child was born – Daniel Tom – and by the time of the 1881 census, the family were living on Ham Hill with John working as a labourer. The family consisted of John and Emma, William from the first marriage aged ten, Daniel aged two and Elizabeth one month. Daniel was to die and be buried in Stoke churchyard two years later. George never knew either Susan or Daniel.

By 1891, John was living in East Stoke with his family. He was 49 and working as a gardener and sexton. Elizabeth (now called Annie) was ten, and the last two sons had arrived: Arthur (baptised Frederick Arthur) aged three and George (baptised Walter George) who was twelve months old.

In 1897, at the age of seven, George became an uncle. Beatrice Annie Regina, daughter of George’s half-brother William, was baptised in Stoke Church. William and his wife Sarah Ellen soon moved to Portland and went on to have six more children. Sadly, Beatrice was the only little girl and she was buried at Stoke in 1898, aged only one year.

With George’s father being a sexton, George would have been brought up with close links to the church but he was obviously not a saintly boy – he is mentioned twice in the school log book:

2nd November 1900 Punished G Ralph and L Bool for bad behaviour

8th February 1901 Punished R Morgan and G Ralph for fighting

George left school and became a stone mason. At 21, he was the last child of the family living at home with his parents in 1911, his father still working as a domestic gardener and sexton, aged 69.

John Ralph was sexton at the church for many years. His name crops up in the Parish Magazine as one of those reliable people who volunteer to help clean and decorate the church, distribute the magazine etc. He was amongst those who collected money for the re-hanging of the bells when the Reverend Monck swept in as a new broom in 1908 and decided that the bells must be re-hung and have a voice again.

G G Monck bought some handbells so that the ringers would be ready when the time came, and in 1910 the handbell ringers – Robert Taylor, Oliver Gale, Hensleigh Male and Arch Thorne, gave a performance under the leadership of Mr T Gale. (Of these handbell ringers, Taylor, Gale and Male were listed on the annual report of the Diocesan Guild of Change Ringers in 1913/14)

Contributions towards the work on the church bells came from, amongst other people, Mr W Ralph (U.S.A.) and Mr Arthur Ralph (U.S.A.) Could the latter have been Arthur Ralph, George’s brother? His half-brother, William Ralph, was in Portland for the 1911 census but I suppose it is possible that he could have been living in America in 1910.

There was a commemorative service for the first ringing of the bells after their re-hanging, and shortly afterwards they were rung muffled for the death of King Edward VII in 1910.

At Christmas time 1910, “The Church Bell Ringers not only on the Church bells awoke the Christmas morn, but with their handbells carried the message of the bells and the festival to every part of the parish.”

On 24th January 1911, the two churchwardens, W Taylor and G Wakely, treated ringers – both Church and hand – to supper on Ham Hill. Amongst those attending were the vicar, Roland and Frank Waterman, G Taylor, A E Bishop, Wm Wakely, Victor Virgin, and Mr J Doble of Taunton who re-hung the bells.

In November 1912, there is the first mention of George Ralph in the Parish Magazine – he was a member of the Committee of the Recreation Society which met in the Church School (now the Church Lighthouse café) every other Tuesday (accompanyist: Mr Jabez Drew.)

In the same month he “contributed to the programme” of a pleasant social evening with the CEMS.

There is no mention of George Ralph in the Parish Magazine as being a handbell ringer, but he took part in a peal to celebrate the wedding of Miss Daisy Jones (Ham Hill) to Mr W F Dimon on 24th March 1913. A peal of Grandsire Doubles 720 was rung by R Taylor (treble), W Warr, G Ralph, H Banbury and T Gale (Tenor). At that time, there were only five bells in the tower, the treble being the present No. 2 bell. It would seem that George Ralph would have been ringing the present No. 4 bell if they listed the ringers in order. “The same company of ringers completed the same peal on Easter day for Evening Service and are to be congratulated on their progress and proficiency.”

At the church service of 1913/14, T Fane (or G Ralph) and T Whitlock were to take the duet and F Comer the solo.

In August 1914, just before the outbreak of War, there is a paragraph in the Magazine:

“We have to thank Mr George Ralph for re-lettering the tombstone of Theophilus Crabbe, the “Intruder” 1675, and also remaking the scratch dial on the church wall which marked the hours for the priest to say his office in the Saxon or Norman period.”

George Ralph was among those who, following in their fathers’ footsteps, were beginning to feature in the life of the Church, when their contribution was cut short by the War. The names, which were beginning to crop up more and more frequently in the Parish Magazine, suddenly stop appearing.

Excerpt from the Western Gazette 1914

England’s Call for Men – Magnificent ResponseStoke had responded nobly to the call for men to serve her in the time of need, 63 young men having volunteered and been accepted which with nine reserves already with the Colours, makes a grand total of 72 up to date, and it is understood that others are volunteering during the week. There have been scenes of great enthusiasm and excitement in the parish daily as the contingents have left by motor car for Yeovil. On Tuesday evening a public meeting for the purpose of stimulating recruiting, was held at the Council School-room, which was crowded by a most enthusiastic audience. Previous to the meeting, the Stoke Band Conductor (Mr G L Dalwood) paraded the principal streets, followed by a procession carrying Union Jacks. The Chairman of the Parish Council, Mr R N Southcombe, presided at the meeting and opened the proceedings with an earnest appeal to the men of Stoke to stand by their country in the hour of need. He read the names of the men who had already volunteered their services, 47 in all. Stirring addresses were also given by Lieutenant Annesley, Colonel Trask, Rev. E Skilton, Rev G O Monck, Mr B Bellamy, Mr H J Fletcher, Sergeant Brake and Mr E D Raymond. The Rev. E Skilton announced that he had been to the War Office and volunteered as a Chaplain. At the conclusion of the meeting, 16 Stoke men and 9 from Norton went to the platform and gave their names, and these left Stoke on Wednesday morning for Yeovil, and later in the day were despatched to Taunton. The meeting concluded by the singing of the National Anthem and cheers for the Volunteers.

George Ralph was one of these early, enthusiastic volunteers. He (along with Percy Trott, Harold Rice, Horace Brooks and Harry Turner) joined the 6th Battalion of the Somerset Light Infantry.

The 6th Battalion of the Somerset Light Infantry was part of the 14th Division which was one of the new divisions of Kitchener’s Army. It was formed of volunteers. Initially without equipment or arms of any kind, the recruits were judged to be ready by May 1915, although their move to the fighting front was delayed by lack of rifle and artillery ammunition.

George Ralph, Howard Rice and Horace Brooks all arrived in Boulogne with their Battalion on 21st May 1915.

Ruined Ypres

The Battles of Ypres were drawing to a close when the 6th (Service) Battalion of the Regiment landed in France. Since the raising of the Battalion in August 1914, the 6th had spent the first three months in hard training at Aldershot. A move was then made to Witley Camp, Godalming, the Battalion returning to Aldershot again in February 1915, where brigade and divisional training was continued until the middle of April. The 6th Battalion, Somerset L.I. was now in the 43rd Infantry Brigade of the 14th (Light) Division, braded with the 6th Duke of Cornwall’s L.I., 6th K.O.Y.L.I., and 10th Durham L.I. A month later (about the middle of May) spare kit had been sent home and all ranks awaited embarkation orders. A few days later they came, and on 21st May the Battalion crossed the Channel in an S.E. & C.R. mail boat and, on reaching Boulogne, disembarked. The night was spent in the rest camp on the hills overlooking the town.

In June, the battalion had its first taste of life in the front line trenches, almost 2,000 yards north east of Wulverghem. The war diary for Sunday, June 13th :“The trench life was very quiet. A little shelling early in the morning and desultory rifle fire during the day.”

After a week of being in the trenches, the war diary says “The Battalion who were our instructors were full of praise of the bearing and behaviour of the ‘Kitcheners’, whom they saw for the first time.”

At the end of June 1915, the 6th Somersets marched to Ypres. George would have witnessed the desolation of Ypres – whole streets of shattered houses.

The 6th Battalion took part in the 2nd Attack on Bellewaarde from 25th to 26th September 1915 – part of the Battle of Loos. The 6th Somersets were attached to 42nd Brigade during this time and afterwards the G.O.C. 42nd Brigade sent the following letter to the C.O:-

“Dear Colonel Rawling, I have to thank you and your fine regiment for the great assistance you gave me on the 25th. It was not an easy thing to reinforce, in broad daylight, as you did, and the movement was exceedingly well and quickly carried out. You arrived at a critical time and your dispositions were exactly what was required. The company of your Regiment which formed the garrison for the trenches rendered valuable assistance and I much regret to hear of the losses they sustained.”

[Somerset Light Infantry 1914-18 by Everard Wyrall]

The total casualties suffered by the 6th Somersets during the month were: officers, 3 killed, 4 wounded; other ranks, 26 killed, 107 wounded.

At the end of October 1915 the 6th Battalion are billeted at Poperinghe. The Diary records: “Spirits of the men splendid. With incessant, rain, plenty of fatigues and no change of clothes and no chance yet of getting warm they can still stand for hours playing and watching football matches.”

Everard Wyrall writes: The first three weeks of November were passed under the most wretched conditions, but on 23rd the Battalion marched to the front-line trenches just north-east of St Jean, relieving the 10th Durham L.I. Two days in and two days out of the front line was the rule at this period, but between the miserable conditions of the billets and the filthy state of the trenches there was little choice. On 14th December the 43rd was relieved by 71st Brigade, the Somersets marching to a camp, described in the Diary as ‘G.5.d’ On 16th the Battalion moved to ‘our old Rest Camp A’ occupied six weeks previously. Here the Somerset men stayed until the close of the year without any incident with the exception of a rumour that the 14th Division was going out to Egypt, which rumour was subsequently dispelled by the receipt of orders for the Division to relieve the 49th Division in the Ypres Salient next to the French.”

I would imagine after the misery of the trenches in winter, the idea of going to Egypt must have been particularly attractive.

The 6th Battalion were not in any more major actions until the battles of the Somme in the summer of 1916. Through the winter of 1915 they suffered “the usual period of torment inseparable from winter in the trenches” (Everard Wyrall). The conditions in the line in January 1916 were terrible. “The front line is in an almost impossible condition and no troops can remain there more than 48 hours without much sickness.” (Battalion Diary)`

In February 1916, the Battalion was just south of Arras. They were in a quiet sector of the line and March passed with very few casualties. In April and May, there was a gradual increase in activity. Shelling became more frequent and snipers claimed more victims. The German 150 lb trench mortars (“Crashing Christophers”, the 6th Somerset called them) were beginning to make life uncomfortable in the trenches.

The actor, Arnold Ridley, describes arriving in France around the middle of March 1916. He writes that the 6th Battalion was in the field just south of Arras. It was heavy, sleeting weather. Ridley was wounded within a few days of joining the battalion and was sent home to recover. He was back in France in July.

He must have been relieved to hear that his Division was not immediately earmarked for battle. In fact it remained near Arras during July, making its way south to the town of Albert, just to the rear of the Somme battlefield, only on 7 August.

Eleven days later, the 14th (Light) Division with the 6th Bn Somerset Light Infantry was pitched into the fighting, Arnold going over the top on 18 August. ‘I fought all the way through Delville Wood’, he later remarked, recalling that even before they set off for the attack, much of the preliminary British barrage had accidentally dropped on them and not on the enemy. Fifteen men were killed or injured.

The concept that surviving an attack was not the end but only a hiatus between actions was hard to accept, and seemed to come as a shock to many men once the enormous adrenalin rush of going over the top finally dissipated…

‘It wasn’t a question of “if I get killed”, it was merely a question of “when I get killed”, because a battalion went over 800 strong, you lost 300 or 400, half the number, perhaps more. Now it wasn’t a question of saying, “I am one of the survivors, hurrah, hurrah”, because you didn’t’ go home….Out came another draft of 400 and you went over the top again.

Delville Wood (15th July to 3rd September)

Delville Wood was sometimes known as Devil’s Wood. It was a tract of woodland, nearly 1 kilometre square. On the west, it touched the village of Longueval, on the east, Ginchy. On 14th July 1916, most of Longueval village was taken by the 9th Division, and on 15th July, Delville Wood was captured by the South African Brigade – all except the north west corner. The South Africans then held on grimly for six days until they were relieved. On 18th and 25th August, the wood was cleared of all enemy resistance by the 14th Division (George’s Division) The fighting at Delville Wood was particularly ferocious.

Harry Turner wrote to his brother, Ernest, “Well, Ern, take my tip and keep out of it if you can. I know for certain that you couldn’t stick it out here. Our Batt has done some splendid work out here lately and have been highly praised for it. You will see a machine gun that they captured on the 18th August on view in Yeovil shortly.”

He goes on to say he has “come across a good few Stoke boys since I’ve been here. I tell you, it’s a treat to see old faces once more. The chaps out here are pretty jolly and we enjoy ourselves pretty well when we are out of the trenches…. Wardle, H Rice, G Ralph and ?C Male are here in the 6th and are all looking pretty fit, except G. Ralph and he’s got thinner than ever.”

According Everard Wyrall’s History of the Somerset Light Infantry 1914 -18:

“After the Battle of Delville Wood, the 6th Somersets spent several days in billets in Fricourt. On the 26th August, however, the Battalion moved forward again to reserve trenches 300 yards in front of Bernafay Wood……. The 28th and 29th were days of great discomfort. Rain fell heavily and the working parties supplied by the Battalion carried on their duties under wretched conditions. Relief, however, came on 30th, the 6th Somersets returning first to temporary billets in Fricourt and then to a rest camp. On 31st, the Battalion entrained at Mericourt for Selincourt, 20 miles west of Amiens where, until the 12th September, all ranks enjoyed a complete rest.”

Then, the Battalion is back in action again in the Battle of Flers-Courcelette – the first battle where tanks were used. It is during this battle that George goes missing.

Battle of Flers-Courcelette – 15th to 22nd September 1916

On 14th September, the Battalion was just south of Albert and began to move up towards the front line. Somewhat sarcastically the Battalion Diary states that at 2 p.m. the Somerset marched off ‘to occupy trenches which did not exist between Delville Wood and the Switch trench’. Here, as no tools had arrived, the men began to dig themselves in, using their entrenching tools. The Battalion were ordered into the front line. No rations had arrived, and so the Somerset men had to go into the trenches without them.

Pen and ink drawing of Tank Battle on

the Somme by Captain Bryan de Grineau.

Lieut.-Col. T F Ritchie (commanding 6th Somersets) was told he was to attack the enemy at 9.25 a.m. on 16th September. No time was given the Battalion for a reconnaissance of the ground over which the attack was to take place and this resulted much confusion. The barrage was also quite inadequate and heavy machine-gun fire met the advance with the result that the attack broke down with heavy losses.

“The casualties of the 6th Battalion in this affair were truly terrible. Every officer who went over the parapet had become a casualty. Three had been killed, 12 wounded and 2 were missing. In other ranks the Battalion had lost 41 killed, 203 wounded and 143 missing. The ridge between “A-A” and “X-X” Trenches was a veritable death trap, and here the Somerset men, as they advanced, were shot down in dozens by German machine gunners firing from the north and east. [History of the Somerset Light Infantry 1914-18 by Everard Wyrall]

At least nineteen of the men from Stoke who died in the 1st World War were in the Somerset Light Infantry, and many of the Stoke men were killed or wounded during the fighting on the Somme in the summer and autumn of 1916. All along Castle Street one could see the blinds drawn in mourning for husbands and sons and brothers.

6th Battalion War Diary for 15th to 16th September

September ALBERT – GUEDECOURT

15th Bombs, 100 rounds S.A.A. per man & Flares were issued. The Battn. moved off at 7.30 and arrived Pommiers Redoubt at 9.30.

11.15 Orders received to occupy the check line in front of Bernafay Wood.

2 pm To occupy trenches which did not exist between Delville Wood and the Switch trenches, men commenced digging themselves in with their entrenching tools as no tools had arrived. The Transport Officer later brought up the tools under heavy shell fire.

11 pm Orders received that we had to relieve the 42 Bde in the front line, but first of all rations had to be fetched about 2 miles back, parties were sent back at once to get rations and water which had not been issued during the day.

1.30 am No rations had arrived so we moved to the front line and relieved the 42 brigade who had attacked in the morning and had received heavy losses. The line was very vague but we managed to get relief over just before daybreak.

War Diary for the day when George went missing

16th September

4.15 Rations only arrived for 2 companies. The other companies ate their iron rations. The worst difficulty was water which was very scarce.

B C A companies attacked Gird Trench and Gird Support supported by D Company but before reaching their first objective, they came under heavy machine gun fire from both flanks which inflicted heavy casualties upon us and we were obliged to dig ourselves in without reaching the objective.

D Company was then sent to the front line but without any further advance. The 6 KOYLI were then called up and kept in reserve in our jumping off position.

Brigade asked us that if we thought it advisable we should attack again at 4 pm, but as we considered it impossible nothing was done.

6.20 Orders were received that the remnants of the battn and 2 companies of the 6 KOYLI would attack Gird Trench again but owing to the short time given us it was found impossible to get orders out, the 2 companies KOYLI attacked as they were already formed up, and a proportion of our men who had received orders but the barrage was again very feeble and heavy machine gun fire was turned on to us, with the result that the attack again broke down with heavy losses. Night had then commenced and parties were sent out to try and collect the various small parties and consolidate the ground won. After great difficulty the trench was discovered. Enough men were collected to hold with the help of one company of the KOYLI. This line was then held and consolidated until relieved by the 13th Batt. Northumberland Fusiliers in the early hours of the morning, just enable the remnants of the b attn to get clear over the crest of the hill by daybreak. Our casualties were every officer who went over the parapet 3 were killed, 12 wounded, 2 are missing. Other ranks casualties were 41 killed, 203 wounded, 143 missing. Operation Orders enclosed with full account.

George was one of the 143 Other Ranks missing on 16th September 1916. Harry Turner and Harold Rice were among the casualties in the battle. Men of Stoke from other regiments were also wounded or killed on that day.

On 20th October 1916, there was the following report in the Western Gazette:

20th October 1916 – Mr & Mrs J Ralph have received information from the War Office that no trace can be found of their son, Pte G Ralph, who was reported missing. It is feared that another brave youth has lost his life in the nation’s cause.

It was not until the following summer that George’s poor parents get official notification of his death. In August 1917, there is a report in the Congregational Church Magazine:

Official notification has come that Pte George Ralph who has been missing so long, was killed on September 16th last. This young man was among the first to volunteer and was 26 years of age.

George Ralph is remembered at The Guards’ Cemetery, Lesboeufs.

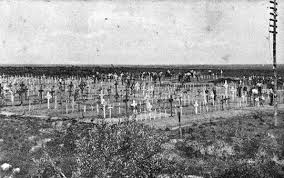

The Guards Cemetery, Lesboeufs,

not long after the end of the War

Lesboeufs Cemetery only consisted of 40 graves at the time of the Armistice, mainly of those officers and men of the 2nd Grenadier Guards who died on 25th September 1916 during the attack on Lesboeufs by the Guards Division. It was greatly increased with graves that were brought in from battlefields and small cemeteries around Lesboeufs.

The following list contains information about George Ralph. Click on the document name to open a pdf of the document.

- RALPH_George Commonwealth War Graves

- RALPH-George-SLI-Battles-of-Somme-1

- RALPH-George-SLI-Battles-of-Somme-2

- RALPH-George-SLI-Battles-of-Somme-3

- RALPH-George-War-Diary-1.9.16-to-25.9-a

- RALPH-George-War-Diary-1.9.16-to-25.9-b

- RALPH-George-War-Diary-1.9.16-to-25.9-c

- RALPH-George-War-Diary-1.9.16-to-25.9-d

Copyright © 2015. All Rights Reserved.