Ringing Bells Through the Ages

by Tom Harris

Church bell ringing is a discipline that has evolved over many centuries and is a particularly English custom. As such it has been exported to those countries around the world where the ‘English’ influence was, in the last three to four hundred years, felt at its strongest. This has resulted in the creation of the typical peals of bells in virtually world-wide distribution. You will be just as welcome as a ringer in the tower in the Christchurch Cathedrals of Oxford, Dublin or New Zealand, as well as in churches in the USA, Canada, Australia, South Africa, and Madrid in Spain and even possibly Poona in India or Lahore in Pakistan. This was all brought about by the accident of global exploration and the expansion of trade routes in the 17th century coinciding as it did with the, by then, firmly established English principle of ‘full circle change ringing’ and the obvious desire of the emigrants to take with them the customs of their homeland. Bells of all shapes and sizes have been rung for a variety of reasons over aeons. There was a time when the use of bells was not regarded as appropriate in church or religious settings, but as the mediaeval ages passed the power of bells to summon parishioners from their homes or work to church services, became recognised as highly persuasive; a sound not to be ignored. In addition they could also be used to broadcast the time of day or announce or warn of imminent events. Until the middle ages and with a catholic church the number of bells for any particular church was strictly regulated and three was considered the general maximum, not to be exceeded without special permission. But even with three bells, ringers had been experimenting with the concept of a more controlled form of ringing rather than simply clattering about in a general melee. The technique, until around the 15th -16th centuries, was either that of hitting the outside rim of the bell with some form of hammer, as is still done today in alarm clocks, or swinging a clapper around on a rope inside the bell. The new concept being explored by this time was that of maintaining a fairly steady clapper and swinging the bell by a few degrees side to side instead. This reached the point, by around the middle of the 16th century, where the bell was mounted on a half wheel and rocked from side to side, the clapper free to swing, while the motion of the bell was maintained by the ringer via a rope attached to the rim of the half wheel. Then came the reformation and the dissolution of the monasteries under King Henry VIII.

It is generally accepted that this event was a ‘defining moment’ in ringing terms. During the dissolution between 1536 and 1540 a large number of surplus bells became available as towers and steeples were razed to the ground. Those experimenting with the mechanics of bell ringing at this time had plenty of examples to work on and various ideas were tried out. The best solution found was that if the bell was attached to a whole wheel, hence the ‘full circle’ bit, there was a point at which the bell, if swung sufficiently, was completely upside down. At this point it could be gently held in place by the ringer and pulled off balance when it was next needed to strike. It would then be swung again by the pull on the rope attached to the wheel rim, through the complete arc, so that it arrived upside down again. Controlled ringing had arrived.

There was now much greater ability to time the striking of the bell, so instead of having bells ringing at random, there developed the system for the controlled ringing of an increasing number of different size and note of bells, ranging from five to twelve or even occasionally today, sixteen. Under pressure to do at least as well as the next-door parish church, individual church bell numbers increased at the end of the 16th century, giving greater variety of sound. In addition around the same time someone also came up with the idea of the stay and slider. This is a simple wooden mechanism that prevents the bell from going over and over in the same direction, restraining it to one full circle swing, first in one direction then in the other. The stay is made of ash while the slider is oak, generally. The reason for this is so that if, as occasionally happens, a bell is pulled too forcibly and the momentum is too great as it reaches the fully inverted position, something has got to give or the whole mechanism is in danger. As ash wood is weaker than oak it is simply the ash stay that breaks leaving everything else intact. A new stay can be fitted relatively easily and cheaply.

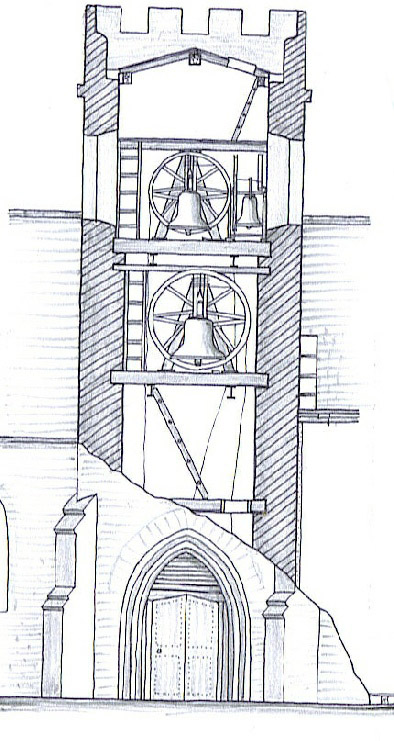

The image illustrates the basic mechanisms of bell hanging and ringing today, incorporating the full wheel and rope attachment together with the stay and slider mechanism.

On the left is the treble bell (6cwt) at the church of St Mary the Virgin at Bishops Lydeard. To the left of the bell is the wheel with the rope attached to the upright, centre spoke and emerging through the garter hole in the rim before descending some 50 feet to the ringer two floors below. To the right above the bell is the stay which will engage with the slider, just visible under the bell, in order to stop the bell going over much beyond the upside-down position. The bell itself is bolted to an iron headstock and the right axle, going into the bearing on the bell frame, can be seen at the base of the stay; the left is hidden by the wheel. The heavy iron clapper inside the bell cannot be seen from this angle.

The 17th century heralded the advent of the classical ringing composers; those who have set the standard for bell ringing composition ever since. Two of the greatest ‘tunes’ ever rung, Stedman and Grandsire, were both composed during this period, once controlled bell ringing had become accepted and the skills needed generally achieved. First, was Grandsire, pronounced as though without the ‘e’, as grand-‘sir’. It is believed this was composed by a member of Charles I court staff, who was dabbling in the new found pastime of bell ringing with other young gentlefolk of the day. As such, if indeed it were Ronald Roan, who as a Clerk to the Pantry of Charles I, this composition was produced in its rudimentary form for a new group calling themselves ‘The Ancient Society of College Youths,’ around the middle of the 17th century and is one of the classics par excellence, of bell ringing methods. Soon after, around 1670, a Cambridge mathematician, Fabian Stedman, composed the ‘principle’ that bears his name following a period of investigation of how, and how many, changes could be rung, on any number of bells, moving each bell only one place at a time and without repeating a sequence. To be able to ring ‘Stedman’ is one of the aspirations of most ringers.

All these things happened soon after St John’s, Staplegrove was endowed with its 5 bell ring, showing how well up with the times even Staplegrove was, right in the vanguard of the new technology of the age, church bells.

Now you would be forgiven for believing that bell ringing was, and always had been, a godly, righteous and sober activity. I must disillusion you, as this was far from the case, but there is good reason, even some very small justification why it was not so.

Here in Staplegrove we have been, and are, very fortunate. It was not always like this. In times past the activities of bell ringers were often in serious discord with the views of the incumbent vicar, churchwardens and congregation. To such a degree that one country curate wrote to his Bishop, near the end of the 19th century, requesting help in dealing with ‘an ungodly set of ringers.’ If we go back, none too far in the past, to the days when the drinking of plain water was accompanied by the considerable risk of contracting a truly serious, sometimes fatal, disease such as typhoid or cholera, bell ringers, in common with a lot of other pastoral workers, were accustomed to drinking beer, or maybe more frequently cider in the west country, simply as a staple form of fluids; and lots of it. Many are the old pictures of a belfry with a large flagon or cask of beer on hand for the ringers. Tea and coffee were expensive and considered the domain of the rich. As a result of this, more often than not, the ringing was augmented with somewhat ribald and raucous behaviour, not in keeping with the dignity required of the office. Indeed, in the 18th century to be a ringer was almost synonymous with being a layabout and a drunk. (Some things never change). Many folk saw ringing as a way to earn an extra bob or two and, ringing being fairly thirsty work, the silver quickly made its way to the local inn. This did not go down too well with the Clergy and Church members, but it went down very well with the local landlord.

It wasn’t always the ringers that precipitated the conflict, however. Sometimes a new vicar was unable to agree, for a variety of reasons seemingly perfectly valid to the incumbent, to the bell ringing custom or customs that had been in place prior to his appointment. Changes subsequently suggested or imposed became strenuously resisted. Sometimes for reasons of religious principle, or even personal preference, some members of the clergy were antagonistic towards ringing. Many were the factors that could create a disagreement, and, with a sense of righteous indignation often went an intransigent posturing, on both sides. When these sorts of conflicts reached impasse, occasionally lock-outs, of the ringers or the vicar, or worse, occurred. On one occasion a vicar found a way of taking legal action “for the misuse of church property” by the ringers, the law definitely being on his, the vicar’s, side, since he technically ‘owns’ the bells. As a result, in court, the ringers were all fined, but being impecunious landed, and languished, in gaol. The fine was paid, some days later, by the Vicar.

It is difficult to understand how anyone can be the least bit ‘under the influence’ and still handle a bell rope and bell with any degree of dexterity, let alone safety. It is a discipline that requires the maximum concentration with total focus on the moment, in order to achieve any degree of competence.

Happily, surrounding and following the ups and downs of both the armed conflicts of the 20th century and the wars of words about behaviour and bell ringing, a balance was achieved. With a sense of propriety dominating behaviour, a harmonious consensus and accord was found and has now stood the test of time, generally, over the last hundred years or so.

It is a great pity that upper levels of our church tower don’t readily lend themselves to visitors. Many parish churches, including St John’s at Staplegrove, have the most beautiful, sweeping views of the local, and in some cases even quite distant, scenery from the top of the tower; views that can be seen from nowhere else. A trip up the tower can be, as they say in the trade, “a nice little earner” too.

Some while ago I was at a coffee morning at St. Elsewhere’s, where there was a ‘donation’ made of £1 per person to visit the top of the tower, and that on a morning when the heavens were open; “come back Noah all is forgiven,” I thought. Yet, despite the conditions, there was a considerable interest in what the inside of the tower looked like, the arrangement that enabled the bells to hang there, and above it all the spectacular view from the very top across the Vale to the Blackdown Hills. Some people even got a rather unusual and different view of their own homes. And the contributions all help in the support of the maintenance of the fabric of the church.

S adly, the historical development of our tower has resulted in there being no dedicated stairway to the bells or the roof, but rather an arrangement of ladders that would seriously distress any Health & Safety Inspector! Nevertheless, that’s what we use to reach the levels in the tower to maintain and service the ringing mechanism of the bells.

adly, the historical development of our tower has resulted in there being no dedicated stairway to the bells or the roof, but rather an arrangement of ladders that would seriously distress any Health & Safety Inspector! Nevertheless, that’s what we use to reach the levels in the tower to maintain and service the ringing mechanism of the bells.

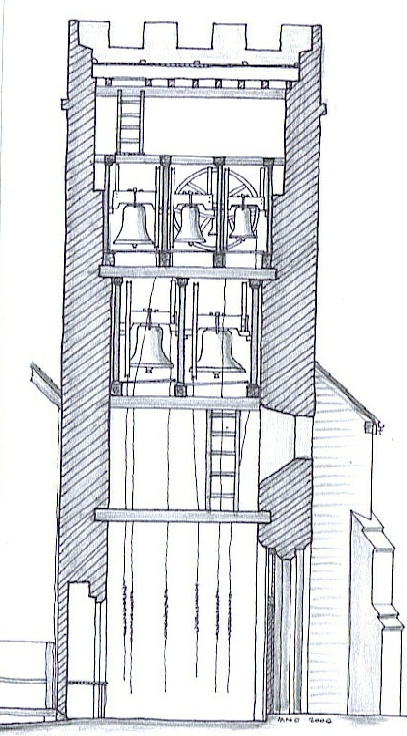

So let me take you on a tour up the tower. The ground floor ringing room was, at one time, the original porch and entrance to the church. The internal arch still bears the pintles of the church door that once hung there and opened into the Church half way along the nave on the south side. Just inside the present outer door there is a ladder. It is solid hardwood and needs to be released from its strap in order to set it so one may ascend skywards to the trap door in the ceiling that allows access to the first floor. Once there this room has no ceiling other than the ultimate roof of the tower itself some thirty feet above. It is a somewhat gloomy, even spooky, place, which indeed requires some degree of athletic ability and contortion to enter from the upper rungs of the ladder. The bells are hung on two levels in the tower. The two largest are on the lower level, roughly behind the clock, and are now just above your head, while the four smaller bells are hung above these two on the upper level.

One of the first things that is apparent are the massive, probably oak, flooring beams that are somewhat curved as they lie. Were they once used for some other function? They are, of course, loose, so that they may be removed should the bells ever need replacing. Then looking upwards through the occasional shafts of light that filter through the few, very small, gothic windows, you see the two largest bells, hanging there some four or five feet above your head, together weighing well over a ton. Adding to the dimness of the interior are the pigeon proofed louvers and wire netting erected in front of the windows. This is, however, quite a spacious area below the bells, apart from the six bell ropes passing through to the ground floor, and a place where we can sit on the floor and work on various aspects of bell maintenance. In the other corner is a second ladder beckoning further exploration upwards.

This is where determined idiocy comes into its own. Going up this ladder requires a degree of gymnastic flexibility that a majority of bell ringers, due to their acquired age and supposed wisdom, lack. After a rotation while actually on the ladder passing the sixth and largest bell you arrive upon the platform of the lower framework supporting the two big bells. For one moment one is also facing the clock electrical mechanism and an inadvertent nudge and the parish immediately goes back to double summer time! It would be no use having a fear of cobwebs, spiders, butterflies or birds, as within the nooks and crannies of the internal tower stone work are most attractive havens for mini-beasts and larger flying things. So, its definitely old clothes on and looking forward to a good shower afterwards, by the time you reach this stage.

One does, being of a certain generation, ponder on the similarities with Charles Laughton in the film as the hunchback, Quasimodo, clambering about the bells in the tower of Notre Dame. With all that however, there is a distinct novelty value to climbing up the ladders, through the maze of huge beams, ropes, wheels and bells, a task only ever undertaken when the bells are at rest in the downward position. There is much boundless poetic licence taken by novelists in the name of creating a good thriller. But the principle remains that when the bells are set upwards, on the balance ready for ringing, they are then in an extremely dangerous position in respect to any passing life forms; half a ton of bell isn’t going to stop for much, once it’s nudged off the balance and on the move!

A fourth ladder takes you to the final internal level, the framework holding the four lighter bells and from which one reaches the glass skylight opening onto the roof. Sliding this back, a few steps up and the castellated parapet is before you. On a bright, sunny morning there can be few better sights than most of Staplegrove village, the Vale and the view to the east, from the Quantocks in the north round to the Blackdown hills in the south. The view to the west is largely blocked by the taller trees of the Grove and the churchyard. The top of the tower here was also a very good vantage point from which to launch our Teddy Bears on their Children’s Festival abseil slide in 2006, because along the west churchyard boundary is the grave of Jimmy Kennedy, composer of ‘The Teddy Bears Picnic’ and also, most appropriately, ‘Red Sails in the Sunset.’